How “The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire)” originated sounds like a piece of fiction. A songwriter uncomfortable in the hot summer of Los Angeles decides to write a song about cold things as a way to cool off.

Yet that is exactly what inspired Bob Wells in 1945 when collaborator Mel Tormé (whose original last name was Torma born of Russian-Jewish immigrants) arrived at his parents’ home in Toluca Lake, an upscale celebrity-inhabited community a short distance from downtown L.A.

When Tormé entered the house, he discovered a 25-word poem (curiously the same number of calendar days leading up to Christmas’s December date) on a writing pad which what turned out to be the opening lines to the song:

Chestnuts roasting on an open fire

Jack Frost nipping at your nose

Yuletide carols being sung by a choir

And folks dressed up like Eskimos

Mel Tormé continues the story in his autobiography It Wasn’t All Velvet:

I took another look at his handiwork. “You know,” I said, “this just might make a song.”

We sat down together at the piano, and improbably though it may sound, “The Christmas Song” was completed about forty-five minutes later.

It wasn’t as quickly recorded though, taking a year before Nat King Cole sang it.

It’s funny how both “White Christmas” and “The Christmas Song” are linked to warm weather in Los Angeles. In Berlin’s verse he talks about palm trees swaying in L.A., and for Wells, it was a 100-degree July day that prompted him to dream of the winter with all its Christmas trappings.

Like a top ten list, the marvel of the song is how it encapsulates so many of the marvelous images and memories people envision about the holiday.

This classic begins with vivid descriptions of what Christmas is all about: “chestnuts roasting on an open fire”—burning wood in the fireplace, “Jack Frost nipping on your nose”—cold weather, “yuletide carols being sung by a choir”—angelic Christmas music, and “folks dressed up like Eskimos”—warm winter clothing. Throw in a turkey, mistletoe, Santa, toys, flying reindeer, and the words “Merry Christmas” and the result is an amazing array of big ideas in a small number of lines that strike an emotional core.

Cole recorded the song four times, the first two recordings occurring within two months of one another.

In 1946, Nat King Cole was known primarily as a jazz pianist as part of the King Cole Trio. While he did sing on the records, his vocals were viewed as secondary to his piano playing.

After hearing Wells and Tormé’s song, Cole felt that strings should supplement the recording.

His widow Maria Cole recalled in her book about her husband how he first regarded the song. “This is a very pretty song but it’s no good for a trio.” It needs “a full band for a big background . . . a different kind of instrumentation.” (Cole 52)

According to Maria, it was Cole’s manager Carlos Gastel (who also had Mel Tormé as a client) who suggested “adding a string section” foreseeing “a new trend for [Cole].”

However, the Capitol Records executives did not see the value of adding to the expense a string arrangement to what they perceived as an intimate jazz trio styling even though Cole had been their biggest recording artist for the past three years.

And so Nat recorded the song just with his trio on June 14, 1946 in New York City at WMCA Radio Studios with a bit of “Jingle Bells” strummed on an electric guitar at the tune’s conclusion.

Once the record company executives heard it, they agreed to add four string musicians and a harpist and the song was completely redone. Cole went back into the studio two months later on August 19, 1946 to re-record it at the same location.

What is intriguing about both 1946 recordings is that Cole misreads the line “to see if reindeer really know how to fly” as “to see if reindeers really know how to fly” adding a grammatically incorrect ‘s’. No one evidently pointed this out to him in the intervening eight weeks between the June and August recording sessions.

Cole finally fixed this error in the successive two recordings.

The third rendering had a lush orchestral arrangement by Nelson Riddle, Frank Sinatra’s top arranger, and was made on August 24, 1953 at Capitol Studios in Hollywood, famously referred to as “The House That Nat Built” due to the amount of money the singer made for the record label. Though rarely heard anymore, music aficionados view this as the best version of the four since Cole’s voice had shown signs of deterioration in the fourth and final recording nearly eight years later.

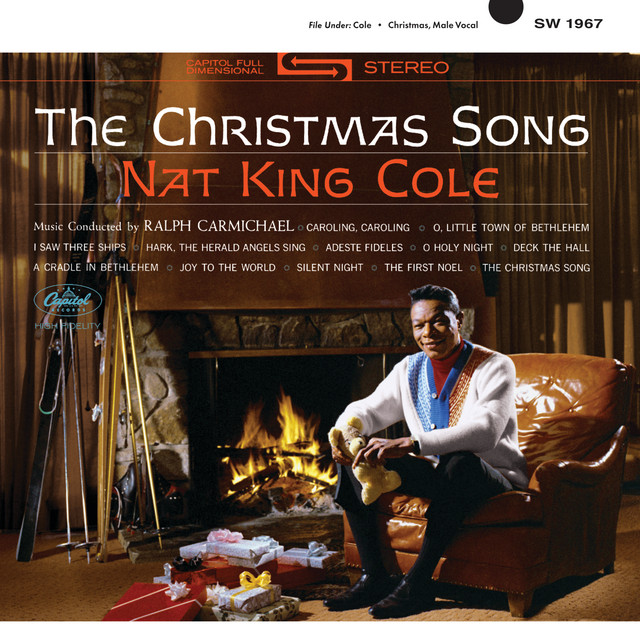

Arranged by Charles Grean and Pete Rugolo, and conducted by Ralph Carmichael, this March 30, 1961 session at New York City’s Capitol Studios is the only stereo recording Cole did of the song which explains why it has supplanted all previous versions, evolving as the one that everyone hears.

While Cole performed piano duties on the 1946 recordings, Buddy Cole (no relation) and Ernie Hayes played the piano on the 1953 and 1961 versions, respectively.

The only reason why “The Christmas Song” was not a number one hit was because at the same time of its release the King Cole Trio’s “I Love You for Sentimental Reasons” was at the top of the charts.

“The Christmas Song” transformed Nat King Cole from a talented jazz artist who sang and played piano in a trio, to a popular singer along the lines of Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra, a master balladeer, an amazing achievement for an African American entertainer at this time. With “The Christmas Song,” the public and the Capitol Records producers heard a different type of singer. From now on, Cole focused his musical skills away from the piano and in front of the orchestra.

As Epstein sums up in his biography of Cole, “For almost a quarter of a century his art had been the art of the ensemble jazz musician. Now he was becoming . . . a lyric soloist.” (158) By 1948, the King Cole Trio as an artistic entity was no more.

Freddy Cole remembers that his older brother “loved the song” and loved to sing it the rest of his days.

Tormé and Wells would eventually go their separate ways enjoying success in the entertainment industry, Tormé donning several creative musical hats most notably as a preeminent jazz stylist, and Wells as a multiple Emmy-winning television producer.

Even though Mel Tormé wrote additional holiday tunes including “The Christmas Feeling” and “Christmas Was Made for Children,” he and Wells never did write a song as popular as they did in 1946. In fact, he often referred to the money earned from the composition as his “financial pleasure.”

The Wall Street Journal’s drama critic Terry Teachout describes “The Christmas Song” as “one of the most harmonically complex songs ever to become a hit.” Still, if it weren’t for Christmas songs of the past airing on radio and in stores each holiday season, few people under the age of 50 would know who Mel Tormé or Bing Crosby were. It is a shame how artists who were once extremely popular over the course of decades can quickly vanish from public awareness.

To further illustrate this, Daisy Tormé, one of Mel’s five children, related a story about her father who was at the storied Farmer’s Market shopping center near Hollywood when carolers strolled by singing “The Christmas Song.” After joining the singers in finishing the song, one of them told him that he “wasn’t that bad of a singer.” When Tormé half-mockingly said that he had recorded a few records in his time, the young man asked, “how many?” “Ninety,” he responded.

One of the main reasons why the song resonates so deeply is the line “and so I’m offering this simple phrase to kids from one to ninety-two,” an unusual use of first person point of view where the songwriter directly addresses the listener.

Daisy wistfully reveals that “every time I hear the song, I get emotional because it is like getting a hug from my father.”

“The Christmas Song” had a career-lasting impact on all three men. This was the biggest hit Nat King Cole, Mel Tormé, and Bob Wells ever had, and it is safe to say that without that song, just as with “White Christmas” and Bing Crosby, the legacy of these men in the 21st century would be diminished if not entirely forgotten.